.png)

THE WW2 PRISONER:

KNIL Army & The Resistance

.png)

DUTCH COLONIAL RULE

Just to have some general details regarding the Dutch Colonial Rule, as it plays a significant role in this entire "chapter", as well as the next, here is a timeline. (All info below from ChatGPT OpenAI accessed June/July 2025):

The Dutch colonized Indonesia for several centuries. Historical Timeline:

• 1602: The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was established. It began dominating trade and politics in parts of the Indonesian archipelago. The Dutch began colonizing Indonesia. The Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) was granted a monopoly by the Dutch government to trade and colonize in Asia.

• 1600s–1700s: The VOC controlled major ports and spice-producing regions, especially in places like Java, the Moluccas, and parts of Sumatra.

• 1619: The VOC established trading posts and gradually took control of ports and islands—most notably Batavia (Jakarta.)

• 1799: The VOC was dissolved due to corruption and debt. Its assets were taken over by the Dutch government, which then made Indonesia a formal colony.

• 1800–1942: In 1800, its territories were nationalized and became a colony of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, officially known as the Dutch East Indies.: The Dutch ruled the colony as the Dutch East Indies, expanding their control to most of the Indonesian islands. The VOC controlled the Spice Islands (Maluku), parts of Java, Sumatra, and Borneo.

• 1942–1945: Japan occupied Indonesia during World War II.

• 1945: Indonesia declared independence after Japan's defeat.

• 1945–1949: The Dutch tried to reassert control but faced resistance and international pressure.

• 1949: The Netherlands officially recognized Indonesia’s independence after a struggle for sovereignty, and transferred sovereignty to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia Serikat), which soon became the Republic of Indonesia.

Summary:

• Start of colonization: 1602

• Full colony: 1800–1942

• End of Dutch rule: 1949

When Indonesia was ruled by the Dutch, its official name was: Nederlandsch-Indië (in Dutch); Dutch East Indies (in English.)

This name was used officially from 1800 to 1942, when the Dutch government took control after the dissolution of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

KNIL: ROYAL NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES ARMY

.png)

Karel Bos served in the K.N.I.L., the Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger (the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army.)

The K.N.I.L. was the Dutch colonial army in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) from 1814 to 1950. The KNIL was responsible for maintaining order and defending Dutch interests in the colony. It was involved in various conflicts and military actions throughout the colonial period. It was composed of both European and indigenous (Indonesian) soldiers.

His rank:

KAREL H. G. BOS: Ls. Sgt. TKL. Inf.: Luitenant KNIL (sergeant Technisch Kader Landmacht Infantrie) (Lieutenant-Sergeant technical corps of the army infantry.)

Military Career

• Rank: Luitenant-sergeant (Senior non-commissioned officer)

• Unit: Technisch Kader Landstorm, Infanterie (TKL Inf) — a technical reserve force within the Dutch colonial militia.

• His professional skills as an architect and engineer were integrated into his military role, possibly involving construction, fortifications, or communications.

I could not find any information (yet) as to the date that he began his military career, or any additional details.

UPDATE February 1, 2026: Per January 2026 communications with the TRACES of WAR website, this is the info share re: the rank of Karel H. Bos:

Dear Elsje,

I contacted Bronbeek about your grandfather's military rank. As I suspected, the rank of Sergeant-Lieutenant did not exist. Bronbeek has a huge amount of knowledge about the KNIL. It is also a retirement home for former military personnel and was originally founded for soldiers from the colony. If you ever visit the Netherlands, I would definitely recommend visiting it. It has a wonderful exhibition about the colonial era without glorifying it. There is also an excellent Indonesian restaurant. Indonesian cuisine is still very popular today.

Then there is your grandfather's rank. They assume that his rank was: LS (Landstorm) Sergeant TKL (second class). In the days of conscription, as I also experienced, Sergeant was the highest non-commissioned officer rank that could be achieved. The Landstorm was a partly voluntary and partly compulsory organization that was founded in 1940 as part of the KNIL. I suppose that, given his age and rank, he was called up for it?

Bronbeek also searched for any other information about his time with the KNIL but was unable to find anything. Much of that information was left behind in Indonesia or lost during the war. They were also unable to find his internment card from the camps. Initially, they thought they had found it, but it turned out to be another Karel Bos from 1903."

Personal Note: It is on my list to contact Bronbeek.

CLICK GALLERY ARROWS BELOW to scroll through the photos.

Karel Bos likely took most of the photos. Unfortunately, I do not know anything about the photos, and am unable to positively identify him, even though there are no more than two "Indos" pictured in most, as the photos are too small.

KNIL Photos from the Personal Album of Karel Bos

THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Indonesia (1942–1945) with the goal to drove out the Dutch. (A simple sentence that changed the course of my family's lives (and thousands of others) forever.

The Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies began in early 1942. The Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) occurred during World War II, from March 1942 until September 1945. The Imperial Japanese Army launched a swift invasion, overrunning the entire colony in less than three months. During the occupation, the Japanese 16th Army government implemented military-political policies emphasizing Dai Tōa Sensō (the Greater East Asia War).

My aunt Joan told me stories about being a child during this time in East Java. She was approximately 9 years of age. She said that everyone, literally everyone, was terrified. Under the Japanese occupation, absolutely no one was allowed to "congregate." This specifically meant no more than two people were allowed to be seen together at any time. Any where. Not even children.

My aunt told me about times when she was out with a friend, and upon seeing their other friends, they dared not say hello or come near each other. They were so afraid that they all looked away from each other in fear of being "caught congregating" by simply saying hello.

NOTICE of the JAPANESE OCCUPATION

Click the button below to read the MARCH 9, 1942 document

of the notice to the citizens of the city of Malang that the Japanese occupation of the city is imminent.

Shared by Achmad Budiman Suharjono.

"The official report of the last days before Malang surrendered to the Japanese military."

This was shared by my "new friend", Achmad Budiman Suharjono.

Click button below to view his website with this historical information, and vintage photos!

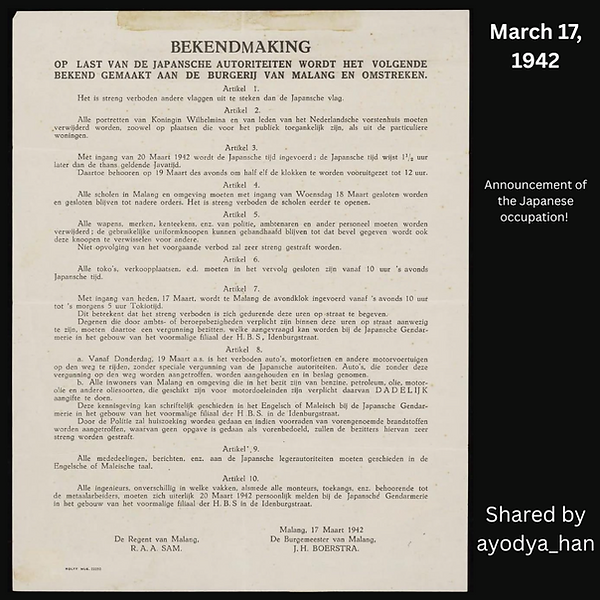

ORDERS ANNOUNCEMENT of the JAPANESE OCCUPATION

Thank you to my "new friend", Han Ayodya, for sharing this historical document!

.png)

Translation of above announcement (from Dutch):

ANNOUNCEMENT

BY ORDER OF THE JAPANESE AUTHORITIES, THE FOLLOWING IS

ANNOUNCED TO THE CITIZENS OF MALANG AND SURROUNDINGS.

Article 1

It is strictly forbidden to display any flag other than the Japanese flag.

Article 2

All portraits of Queen Wilhelmina and members of the Dutch Royal Family must be removed from both public places and private residences.

Article 3

Effective March 20, 1942, Japanese time will be introduced; Japanese time is one hour later than the current Java time. This includes setting the clocks forward to 12 noon on March 19 at 10:30 p.m.

Article 4

All schools in Malang and the surrounding area must be closed effective Wednesday, March 18 and remain closed until further notice. Opening schools earlier is strictly prohibited.

Article 5

All weapons, brands, insignia, etc., of police, civil servants, and other personnel must be removed; the usual uniform buttons may be retained until an order is given to exchange these buttons for others.

Failure to comply with the foregoing prohibition will be severely punished.

Article 6

All shops, sales outlets, etc., must be closed from 10:00 PM, Japan time.

Article 7

Effective today, March 17, a curfew will be in effect in Malang from 10:00 PM to 5:00 AM, Tokyo time.

This means that it is strictly forbidden to be on the streets during these hours.

Those who are required to be on the streets during these hours due to official or professional duties must have a permit, which can be requested from the Japanese Gendarmerie in the building of the former H.B.S. branch on Idenburgstraat.

Article 8

a. Starting Thursday, March 19th, it is prohibited to drive cars, motorcycles, and other motor vehicles on the roads without a special permit from the Japanese authorities. Cars found on the road without this permit will be stopped and confiscated.

b. All residents of Malang and the surrounding area in possession of gasoline, kerosene, oil, motor oil, and other oils suitable for motor use are required to report this IMMEDIATELY. This notification can be made in writing, in English or Malay, to the Japanese Gendarmerie in the building of the former H.B.S. branch on Idenburgstraat. The police will conduct searches, and if stocks of the aforementioned fuels are found that have not been reported as aforementioned, the owners will be severely punished.

Article 9

All communications, messages, etc., to the Japanese military authorities must be in English or Malay.

Article 10

All engineers, regardless of their profession, as well as all mechanics, accesses, etc., belonging to the metalworkers, must report in person to the Japanese Gendarmerie at the building of the former H.B.S. branch on Idenburgstraat no later than March 20, 1942.

The Regent of Malang,

R. A. A. SAM.

Malang, March 17, 1942

The Mayor of Malang,

J. H. BOERSTRA.

INTERNMENT of ALL WHITE, PURE DUTCH

Click the button below to read the NOVEMBER 10, 1942 document of the "Declaration of Internment blanda-totoks" in Malang.

(Internment declaration of the white, pure Dutch)

Shared by Achmad Budiman Suharjono.

K. BOS in THE RESISTANCE

There was resistance against the Japanese occupation in East Java during World War II (1942–1945), although it was limited, fragmented, and often covert due to the brutal repression by the Japanese military authorities. Some Dutch loyalists, Indo-Europeans (Indos), and former KNIL (Royal Netherlands East Indies Army) members engaged in low-level sabotage, or sheltered escapees or prisoners of war. This was risky, as the Kempetai (Japanese military police) were known for torture and execution.

The Japanese Kempeitai (military police) ruthlessly hunted and tortured suspected dissidents. Anyone caught aiding resistance could face execution, torture, or mass reprisals (sometimes whole villages were punished). As a result, most resistance was cautious, secretive, and localized. Major uprisings were rare until the final months of the war.

In Malang and Surabaya, there were clandestine networks that resisted Japanese control and later re-emerged during the 1945 revolution. Their activities were mostly covert education rather than open armed resistance (which was nearly impossible under Japanese rule).

Karel Bos became involved with the local resistance in East Java. While detailed records of his activities are scarce, it is well-documented that he joined movements resisting Japanese control, and that he was arrested by the Japanese Occupation. He was said to have been a trusted leader of the resistance.

At this time, there were two forms of resistance: 1.) Resistance against the Japanese Occupation, and 2.) Resistance by (non-Dutch/non-European) Indonesians against the Dutch rule. They believed in "Indonesia for Indonesians."

While direct quotes are lacking, Bos aligned with the ideologies gaining ground in 1942–43 East Java—when underground cells formed in dozens of towns, including Malang, to challenge Japanese rule. Karel H. Bos was not just an architect — he also became involved in the resistance against the Japanese occupation during World War II. He was arrested by the Japanese for his "alleged" underground activities.

His architectural legacy translates into the resistance era as discipline, leadership, and functional planning skills, all of which peers likely valued in clandestine operations. Contemporaries respected him as “one of the leaders … whose authority was unchallenged” among resistance circles—particularly due to his organizational abilities and moral conviction.

His belief in freedom from the Japanese occupation was clear in his alignment with grassroots resistance networking, despite the risk. Most clues lie in Japanese records, his execution, and the underground network he was part of.

Involvement in the Resistance

• During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies (1942–1945), Bos became involved in the underground resistance movement.

• Bos was a respected, trusted, principled leader. Officers of the Japanese occupation considered him a serious threat, reserving execution for individuals “whose authority was unchallenged” in local resistance activities. That level of attention suggests Bos was deeply respected within his circles.

• The resistance comprised Dutch military personnel, colonial civil servants, professionals, and civilians united to oppose Japanese rule.

• Bos’s expertise was leveraged in clandestine efforts including sabotage, intelligence gathering, and coordination among Dutch and Indo-Dutch networks. His architectural legacy translates into the resistance era as discipline, leadership, and functional planning skills, all of which peers likely valued in clandestine operations.

• He was known to have participated in secret meetings with fellow professionals and military officers in Malang and the surrounding region.

• Bos’s arrest and execution in Bondowoso in 1943 reflect how seriously the Japanese perceived him. He wasn’t a low-level saboteur—he was someone believed capable of organizing significant threats.

(All above info = Sources: ChatGPY OpenAI accessed June 2025; Google AI accessed June 2025)

The article in the button link below was shared with me by Achmad Budiman Suharjono.

The article appeared in the Dutch magazine, TONG TONG, on August 30,1962.

The title of the article =

"List of people who participated in the underground resistance in the former Dutch East Indies and were executed, or died as a result of torture.

(Yes, the name K. H. G. BOS is indeed on this list, #53. See article snippet below.

For the full article, click the button.)