.png)

THE WW2 PRISONER:

Capture & Internment Camp

THE KEMPEITAI

During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) during World War II, the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, had a significant presence and role in Java, including East Java.

The Kempeitai were a powerful and feared force responsible for enforcing Japanese authority, maintaining law and order, and suppressing any form of anti-Japanese resistance in occupied territories. They used extreme brutal tactics, including torture and arbitrary arrests, to control the local population and ensure compliance. The Kempeitai acted more like a secret police force similar to Germany's Gestapo.

Words that have been documented in describing the Kempeitai: "Brutal", "sadistic", "torture", "beatings", "starvation", "forced physical labor under unbearable conditions", "cruel", "barbaric."

The Kempeitai:

-

Diverse Duties: Their duties extended beyond traditional military policing and included:

-

Counterintelligence and counter-propaganda.

-

Enforcement of conscription legislation.

-

Recruitment of labor and requisitioning of supplies.

-

Suppressing anti-Japanese sentiment and resistance.

-

Operating prisoner-of-war camps.

-

Conducting interrogations, often using torture.

-

-

Brutality and Atrocities: The Kempeitai were notorious for their brutality and involvement in war crimes. This included:

-

Torture and summary executions.

-

Reprisal raids and massacres of civilians.

-

Forcibly conscripting women to serve in military brothels (comfort women).

-

Procuring human subjects for medical experiments at facilities like Unit 731.

-

Their actions left a lasting impact on the local population and underscore the dark side of the Japanese occupation during World War II.

CAPTURED: TAKEN PRISONER

I will never forget the day sitting on my couch with my aunt, Joan Bos, while she was visiting me at my (then) home in California in 2015. (It would be her very last trip to the United States.)

As was with every visit together over the decades, we would find ourselves talking about her memories of her father and her life in Malang. On this particular instance, she had just passed down to me her father's photos, postcards, and memorabilia which she had been holding on to for over seven decades.

I had asked her when the last time was that she saw her father. Her eyes and body dropped as she was telling me about being outside one day, and seeing the train approaching. She said she was looking in the windows of the train as it rolled by as she always did. And then she saw him. Her eyes locked with the eyes of her father. He wasn't smiling as he normally would when he saw her. Their eyes stayed connected to each other's until the train window was no longer in sight.

As she was telling me this, her body dropped further, her speech became very slurred, then stopped. She was no longer making eye contact and her mouth was drooping. Her head slumped over and she was no longer responsive. I thought she was having a stroke, and picked up my phone to call 9-1-1-. I was so scared. I yelled, "JOAN!" And then she started coming to.

She quickly became alert again, and explained to me that she has suffered from narcolepsy her entire life. (It was always the family joke how she could fall asleep anytime, anywhere. Now I knew why.) She also explained that her physical reaction to the emotional overload in retelling the last time she saw her dad was actually a common symptom of those suffering with narcolepsy. She had actually fallen asleep while telling me this story!

It. was. the. last. time. that. she. ever. saw. her. father.

He had been taken prisoner by the Kempeitai.

He was taken to the Kesilir Internment camp along with a train full of others.

According to a document from KESILIR (click button below), there were 120 men taken prisoner from Malang and transported to Kesilir Internment Camp on July 22, 1942. It was a Wednesday. (A ChatGPT Open AI response suggested that he was likely taken from in or near his office.)

(I don't know exactly where Tante Joan was when the train went by with her father, but I was able to find these circa 1935 photos that show train tracks in the areas where they used to live.)

KESILIR INTERNMENT CAMP

The Kesilir Internment Camp was primarily (but not exclusively) for men. It held mix of military and civilian prisoners, and was notorious for harsh conditions and the detention of political prisoners and resistance fighters. Kesilir Internment Camp was well known for brutality.

Historical records indicate that during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, beginning in early 1942, Japanese authorities implemented policies to intern European civilians, including Dutch nationals. In the summer of 1942, the Japanese decreed the relocation of all Caucasians and Dutch citizens into prison camps, who were subjected to harsh conditions.

The reasons for his capture were said to be the suspicions of his role in the resistance. It is possible that as a well-educated and potentially influential individual, he may have been suspected of leadership or communication roles, even without evidence.

Of the people that were imprisoned at Kesilir along with Karel H. Bos, some were likely colleagues or associates. Here is a list of prisoners that he may have known prior to his imprisonment:

-

Adriaan Bos — Given the shared surname, it is quite plausible he was a cousin or other relative. This suggests a close personal connection rather than just a professional one. (I am still researching this.)

-

Carel Frederik Lans and Lucien Jean Oudkerk Pool — Both names appear in Dutch-Indonesian colonial records as professionals or civil servants active in East Java around that time, potentially in similar administrative or technical roles.

-

Hendrik Esser and Jan Hubert Mussers — These names are linked in some accounts to the Dutch civil engineering or architectural community in the Indies, making them possible professional acquaintances of Karel Bos.

-

Diederick F. D. van den Dungen Bille — A known figure who served in technical or military roles in the Dutch East Indies, possibly connected to the same Landstorm unit or resistance circles.

The Japanese established Kesilir as an experimental agricultural colony on Java’s easternmost coast, spanning 40 km², surrounded by barbed wire. Its goal was to become self-sufficient with up to 70,000 people. Around 3,000 male prisoners (mostly Dutch and Indo-Europeans) forcibly worked there for roughly 15 months. This camp held a mix of civilian and military prisoners.

Survivor testimonies highlight Karel Bos’s courage and steadfastness in captivity.

(Source of all above info = ChatGPT OpenAI accessed June/July 2025)

From his postcards, we know that he was in "Percel no. 11." (Parcel/Lot #11.)

.png)

THE POSTCARDS!

Considering the cruel and sadistic nature of the Kempeitai, it truly blows my mind that the prisoners were allowed to write and send postcards home at all.

That said, this is what is known: Dutch civilians and military prisoners were often severely restricted in communication with the outside world. However, some limited correspondence was allowed under strict censorship. Personal expression was severely limited. Prisoners often had to write things like “I am well” or “All is fine” even if it wasn’t true. These letters often gave false impressions of safety or wellbeing, because any mention of poor treatment, illness, or torture would result in the letter being destroyed and the prisoner punished.

Delivery was unreliable. Many letters were lost, delayed, or never reached their destination due to wartime chaos and censorship.

What a blessing that at least these three postcards made their way to family. They were amongst my aunt Joan's most prized possessions, and now they are amongst mine.

(In the second postcard, Karel Bos says that they are only able to write once a week. I can only assume that he did. I can only assume that the other postcards never made it to the family.)

(Thank you to Agiesta W. Adhitara for helping me with the years! And thanks to Achmad Budiman Suharjono for sharing that the street name Oro Oro Dowo is now called Jalan Brigjend Slamet Riadi.)

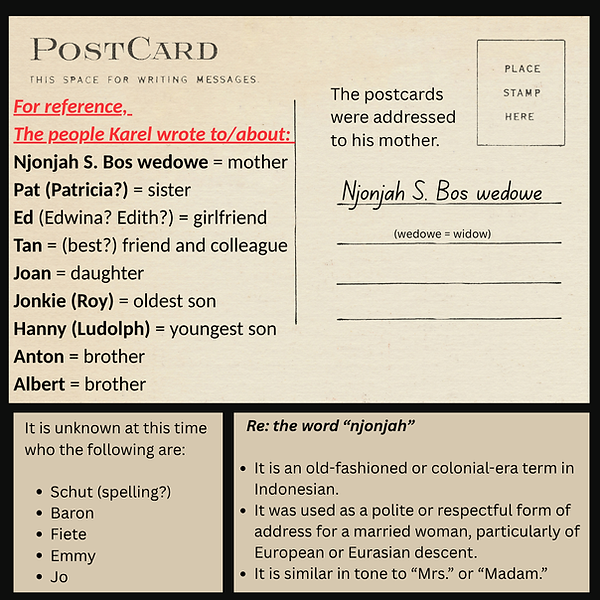

Translation of above postcard (#1 of 3) from Indonesian to English by Joan H. Bos 2015

(Translation Side "a")

Kesilir 18-26 2602

August 5, 1942

Children, Joan, Jonkie and Hannie,

If you have already received a message from daddy, please write him, yes? Then ask your mom for you stay with Ed, so Ed will not stay alone. Don't be naughty, but think of daddy. Ask if you can send me cigarettes. With Ed for not so much. Bye my children, think of me.

Daddy

(Translation Side "b")

Dear Mama and Pat,

I have send twice a postcard to Ed but I have heard no response. Did Ed already move from the house. Where is she now. Help me to ask my children if they are with their mother. Send me as fast as you can a message about this. Here I'm blessed and OK, don't worry about my problems. If you can tell Ed, not to leave the house. Ed should ask money to B.G. Tan and Schut, and ask Ed some for the children, also if she can send me some shopping and post card and stamps, they are hard to get here. Mom and Pat stay healthy. Help Ed please she is alone. Many Kisses for everyone. Karel

PS Ask some help to Baron

Translation of above postcard (#2 of 3) from Indonesian to English by Joan H. Bos 2015

(Translation Side "a")

Kesilir 31/8.02

August 31, 1942

Dear Tan are you okay. I am only worried . Would you please help me with my children and vrouw (woman) in this the time. I am staying now Kesilir. I’m really worried Tan. I can only think about my vrouw (woman) and children. That they don’t feel like I do.

Many Greetings, Karel

(Translation Side "a")

Dear Ma and Pat, your post card I did received I can now. I did write Ed. Every week we are only allowed to write time. The stuff Ed send my I received 8/29. Okay mama and Pat it is good to hear that you are and watching over Ed and my children, it makes me happy to hear that. If Ed can let her send me some food and dry meat, some pork dried. Smoked. The other are not important any more. Now I'm really black from the sun, but now my body is strong. Don’t let Ed read this card. Give my blessing to Fiete but don't let her add more to what happened before. If you can try to get in touch with Baron T. I wrote in the back to mister Tan Bouwkund, and Ed should send this to him. Stay happy mama and Pat and think about my children, they are still small.

Don't worry about me, many kisses, Karel

Translation of above postcard (#3 of 3) from Indonesian to English by Joan H. Bos 2015

(Translation Side "a")

24/.03

August 24, 1943

Joanie, Jonkie and Hanny, are you still nice and do you eat good. Keep growing big and fat. Many kisses from Daddy

(Translation Side "b")

Dear Ma and Pat

Is everything still okay this moment, no more problem with your eyes. How is it now with Anton and Albert. Did you already receive some news about them. I've not received a card in a long time from Ed. Hope she is okay. I just wrote her to take care of my house.

Try to ask Ed why she does not write me. How is it going with your work Pat. I feel good to hear Pat you broke off with Eddy. Pat help me to tell Emmy. She let me know about (????) in Glintoeng. I also got a message from Jo that she has moved. Well Mama and Pat many greetings and kisses from Karel.

.png)

MORE ABOUT THE STAMPS

-

Japan replaced Dutch postal systems and stamps with its own.

-

Japanese authorities issued occupation stamps specifically for use in Indonesia. These stamps usually included the words “DAI NIPPON” (大日本), meaning “Great Japan”.

-

Featured propaganda-style imagery or local motifs, as seen in these stamps with animals and tropical scenery.

-

Sometimes retained local currencies (like cents or gulden) for practical use.

-

These stamps were used for postal services under Japanese administration, including: Civilian mail, Communication within the occupied territories, Censored or regulated mail to maintain control over information.

-

These occupation stamps became obsolete after Japan’s surrender in August 1945.

-

They are now historical artifacts and collector’s items, often studied for insights into wartime governance and propaganda.

KESILIR ARTICLE

Note: While my grandfather was not amongst those who died at Kesilir, he was amongst those who suffered there. The article acknowledges this internment camp, and lists those known to have perished there.

Translation of above article (from Dutch):

Deceased of the Kesilir Internment Camp

The Head of the Branch Office SOERABAJA of the INVESTIGATION DECEASED SERVICE, Mr. J.W.F. MEENG, requests to inform us of the following.

As may be assumed, the agricultural colony KESILIR, which is located southwest of Banjoewangi, was used by the Japanese occupiers as an international trade camp used for European internees.

The internees who died in the KESILIR internment camp are buried in the PESANGGARAN cemetery, located 4 KM from that former camp.

During an investigation, which was conducted on site by the O.D.O. it emerged that the following internees were buried there, namely:

The name of one deceased person has not yet been traced, while according to information obtained from the Pesanggaran petinggi, shortly after the first police action, the remains of an unknown internee were exhumed by a person of Ambonese nationality and taken to Malang. Those who can provide information about the name of the aforementioned, unknown survivor Danes, are urgently requested to contact the office of the Deceased Persons Investigation Service (0.0.0.) c/o

the Residentiekantoor here.

Finally, the surviving family relations are requested, to as far as this has not yet been done, to also contact the O.D.O. office Surabaya to obtain a death certificate.

(See image #2 above for list of names.)

LIST of INTERNMENT CAMPS on JAVA

Here is a list of all Internment Camps on the island of Java, run by the Japanese occupation.

(Note: From what I gather, these are a list of "INTERNMENT CAMPS" only. The two Bondowoso camps listed are not the same as the "PRISON CAMP" where Karel H. Bos and others were transferred to and held.)

-

Scroll down for "Oost Java" (East Java) within the table. Click on KESILIR. (Note: After clicking camp location, there is an option to switch to English translation, however, translation also listed below.)

-

Scroll down farther on the list and click on "OOST JAVA" below the table to see a map of the internment camps.

Thank you to Achmad Budiman Suharjono for sharing another great piece of information!

TRANSLATION OF KESILIR INFO:

Camp Location

The Kesilir experimental agricultural colony was situated on the south coast, almost at the easternmost tip of Java. The entire colony was spread over a very large area (approximately 40 square kilometers), completely surrounded by barbed wire. The camp was housed in homemade shelters and barracks.

The intent of the Japanese occupiers (General Imamura) was to establish a large-scale, self-sustaining agricultural settlement for 70,000 persons (men, women and children). About 3,000 men worked here for 15 months. The project failed due to a lack of farming know-how and tools with which to work. The men were about 70% European and 30% Indo-European. They cultivated corn, soybeans, green peas and other vegetables.

Japanese Camp Commander

Takahashi

Dutch Camp Leader

Mr. J. G. Wackwitz

Table & info is NOT translated below, except for the line that relates to Karel H. Bos:

Transports (source: Atlas Japanse Kampen):

DATE: Apr. xx, 1943

ARRIVED FROM: (blank)

TRANSFERRED TO: Bond: Kempetai (5)

NUMBER IN TRANSPORT: 38

TOTAL NUMBER IN CAMP: (blank)

INDIVIDUAL TYPE: b,m

Abbreviations / Notes: b=boys, m=men; Bond=Bondowoso

References

Beekhuis, H. et al - Japanse burgerkampen in Nederlands-Indië, Volume 2, pp 113-114

Br J. van der Linden FIC (Brs van Maastricht) - Donum Desursum, privately published, 1981, pp 74-77

Brugmans, I.J. - Nederlands-Indië onder Japanse bezetting, p 462 (Pagi-groep)

Dulm, J. van et al - Atlas Japanse Kampen, Volume I, 2000, p 181

Jong, L. de - Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in WOII, Volume 11B, 1985, p 341, p 821

Jong, L. de - The Collapse of a Colonial Society, 2002 (Engelse vertaling van Deel 11B)

Marsman, Harryet - Klapperolie voor Kesilir, Moesson magazine 14/3 (July/August 1996), pp 40-41

Moscou-de Ruyter, M. - Vogelvrij, 1984, pp 30-115 (visiting women from Malang)

Smit, H. - Onderbemingsleven in Nederlands-Indië, 1977

Smit, H. - Van katjong tot rijksambtenaar, Moesson magazine, 1982, pp 85-150

Soesman, J. - Verslag Rode Kruis-afdeling Malang, July 6, 1946, NIOD, IC-004397

Stutterheim, John K, - The Diary of Prisoner 17326, 2010, Chapter 7 (“Kesilir”), pg 41-48

Veldhuijzen, Han - De trein van Kesilir naar Tangerang, Moesson magazine 41/4 (Oct. 15, 1996), pp 22-23

Verslag “Belevenissen en gebeurtenissen in Indië tijdens de oorlog”, 1945 (Archive of the Broeders van Dongen)

Wackwitz, J.G. - Kesilir, July 1942 - September 1943, Moesson magazine, 1988

Willems, Wim en Jaap de Moor - Het einde van Indië, 1995, pp 113-126 (Huub de Jonge text)

Wolff-Werner, Helga - Bezoek aan Kesilir, Moesson magazine 35/2 (August 15, 1990), p 9

Photographs / Drawings

Claassen, Rob en Joke van Grootheest - Getekend, 1995, pp 108-110

Warmer, Joh.A.G. - Java 1942 - 1945, Kampschetsen, 1984, pp 7-53

Camp Map

Beekhuis, H. et al - Japanse burgerkampen in Nederlands-Indië, Volume 2, p 114

Dulm, J. van et al - Atlas Japanse Kampen, Volume I, 2000, p 181, Volume II, 2002, p 151

KESILIR CAMP LEADERS

From the above report, the names of the camp commander and leader are now known.

Here is the information I was able to find about each of these leaders.

RE: DUTCH CAMP LEADER: Mr. J.G. Wackwitz (source = Google AI)

Mr. J.G. Wackwitz was the Dutch camp leader at Kesilir, Java (Dutch East Indies) during its period as a Japanese internment camp (July 1942 - September 1943).

Based on a report by J.G. Wackwitz written in 1946, it is known that the prisoners at Kesilir, around 70% European and 30% Indo-European, were forced to cultivate crops like corn, soybeans, and vegetables, but they lacked proper tools.

Conditions at Kesilir internment camp under J.G. Wackwitz

Reports and accounts, including one by J.G. Wackwitz himself, paint a grim picture of conditions at Kesilir internment camp during the Japanese occupation:

-

Overcrowding and inadequate facilities: Prisoners were housed in makeshift barracks-style accommodations, often sharing limited space with multiple families, leading to a lack of privacy and discomfort.

-

Poor sanitation and hygiene: The report by the 120th US Evacuation Hospital noted "disastrous sanitary conditions", including a lack of proper latrine facilities and poor overall hygiene within the camp after liberation. While this report details conditions after the Wackwitz era, it suggests a pre-existing problem with sanitation and its impact on prisoner well-being.

-

Forced labor and limited resources: Prisoners were compelled to cultivate crops with inadequate tools, impacting their ability to sustain themselves, according to a report by J.G. Wackwitz.

-

Food shortages and malnutrition: Food became increasingly scarce in the camps, leading to widespread exhaustion and malnutrition, resulting in a high mortality rate among detainees, with approximately one in eight dying due to these conditions.

-

Harsh regulations and punishments: The Japanese tightened rules and restrictions, imposing roll calls, forced labor, and severe punishments for infringements. They also banned valuables, leading to confiscations.

-

Restriction of movement and lack of freedom: Barbed wire fences surrounded the camps, and guards patrolled, enforcing restricted movement and denying the internees their freedom.

-

Limited medical care and outbreaks of illness: Poor sanitation, overcrowding, and lack of resources created a breeding ground for infectious diseases and viruses, with limited medical staff and inadequate facilities struggling to cope.

In essence, life in Kesilir was characterized by severe deprivation, harsh treatment, and a constant struggle for survival against disease, hunger, and restricted freedom.

SKETCH by KESILIR PRISONER

.png)

SKETCH by KESILIR PRISONER

.png)

.png)